We acknowledge all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first sovereign people of this land.

As a community of educators, we recognise with deep respect their continuing connections to lands, waters, knowledges and cultures. In doing so we pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Module 3.1: Getting started in this module

Objectives of the module

This online module will strengthen teachers’ understanding of assessment as part of an effective planning cycle that identifies play and inquiry learning outcomes in relation to the Victorian Curriculum (F – 10). This includes assessment in curriculum areas such as language and literacy, numeracy and mathematics, as well as personal and social capabilities. The module also focuses on assessing play itself, recognising the link between a student’s play ability and learning.

Listen to this welcome vodcast where Professor Andrea Nolan will introduce herself and the other academics who will be facilitators for this module.

Authentic assessment captures the learning

Authentic assessment captures the learning as it occurs naturally. During play, students naturally apply skills, abilities, knowledge and understandings. As noted in the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF): practice principles guide – high expectations for every child (PDF, 430KB), authentic assessments take place in environments that are familiar and natural to children; when children are comfortable; when children can engage with experiences, materials and equipment that interest them; and in everyday experiences.

‘Assessment of children’s knowledge, understandings, skills and capabilities is an essential ingredient of planning for and promoting new learning and development’ (VEYLDF 2016). By observing students during their play and documenting what you see, you can gain a rich understanding of what they know, understand and can do. For example, during play, pay attention to the kinds of behaviours the students engage in and their interactions with materials, objects and people. Observe these behaviours for:

- signs of progression in their learning

- achievement against learning intentions and success criteria

- new abilities

- student enjoyment in accomplishment.

Resources for authentic assessment in the early years

Outcome descriptors in transition learning and development statement

When considering authentic assessment and planning of play-based and inquiry learning, you may find it helpful to consider the outcome descriptors captured in transition learning and development statements(opens in a new window). The descriptors (PDF, 318KB) describe a child's progress against the five learning and development outcomes of the VEYLDF and are aligned with the first three levels of the Victorian Curriculum (Levels F-10).

Early Abilities Based Learning and Education Support (Early ABLES)

Early ABLES(opens in a new window) is a strengths and observation-based online assessment for learning tool. It supports educators to provide a more individualised learning experience for children aged two to five years with disabilities and/or developmental delay. This assessment tool is particularly useful for students requiring an enhanced transition to school.

Early ABLES includes eight assessments that align with the learning and development outcomes of the VEYLDF:

- Identity and community – social

- Wellbeing – emotion

- Learning dispositions

- Communication – interactions

- Communication – symbols and text

- Learning and communication – numeracy

- Wellbeing – movement

- Identity and learning – thinking skills.

Examples of assessment from practising teachers

Watch the below video about examples of assessment from practising teachers.

As you watch the video consider the different perspectives of assessment that are discussed and their potential.

Connecting with parents about assessment

Teachers choose assessment instruments and techniques to create a holistic picture of each child’s knowledge, understandings, skills and capabilities. Teachers also consider how they can support parents/families to understand and value the learning that comes from play in a play-based and inquiry learning program. This means being thoughtful, deliberate and purposeful in the way the information is utilised in discussions with families.

Watch this video about connecting with parents about assessment, where a Foundation teacher outlines how she and her colleagues demonstrate learning and student progression to parents.

Sharing information with parents can assist in building their understanding of the learning that is occurring in play and that play is purposeful with goals and expectations that students can achieve.

Module 3.2: Different types of assessment

Assessment and documenting learning

This section will assist you in thinking through how you assess, which directly relates to what learning the assessment will capture. Play provides a vehicle where students can demonstrate their skills, understanding and learning. During play, assessments can be made in relation to their progress in curriculum areas, as well as their play ability. This is discussed further in the next section.

Documenting learning in play-based and inquiry learning can take the form of observations, portfolios, video and audio recordings, work samples, anecdotes, language transcripts, running records and student self-reflections. This is not an exhaustive list but demonstrates the variety of tools teachers can use to identify and document the learning outcomes achieved through play-based and inquiry-led experiences.

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Questions for learners and teachers

Teachers should be able to explain to the learners:

- What is to be learnt - the learning intentions?

- How are the learning intentions linked to the bigger ideas and understandings that the learners will learn?

- How will the students be learning?

- How are the learning activities relevant to the success criteria?

- How will learners demonstrate their learning? What will they say, make, write or do with reference to sample assessment tasks?

- How will this new learning impact on future learning?

Downloadable version of questions for learners and teachers (PDF, 114KB)(opens in a new window)

Downloadable version of questions for learners and teachers (DOCX, 24KB)

Three types of assessment

Assessment is powerful and diverse. It supports teachers to understand what students know, to enable them to guide their own learning and shape teaching practices.

Type 1: Assessment of learning

Assessment of learning summarises what students know, understand and can do at specific points in time. These can be large-scale such as NAPLAN or individual teachers using evidence of students learning, to inform their practice decisions such as the transition learning and development statements(opens in a new window).

Type 2: Assessment as learning

Assessment as learning positions students as actively involved in assessing their own learning through the support and development of their metacognitive skills. When students are involved in self-assessing, thinking and monitoring their own progress on what and how they learn, it can give them a sense of ownership and help them take more control of their own learning as they interact with teachers and peers. This positions students as capable and competent learners, who are supported to learn more about what they learn, and what they would like to learn. In this way, the process of assessment is a learning experience in and of itself.

Type 3: Assessment for learning

Assessment for learning views assessment and teaching as intertwined and not separate from each other.

Student learning is shaped by the teachers’ use of practices such as questioning and the provision of timely feedback.

It is considered a continuous process, involving teachers finding out what students know, understand and can do, and then modifying their teaching to help students to be successful on a daily basis.

This enables teachers to refine their teaching approach, build on students' previous learning and support new learning. It is ongoing and occurs in context. This is formative assessment.

Assessment for learning is the only form of assessment ‘which extends students’ learning because it enhances teaching. All other forms of assessment serve as checks on whether or not learning has occurred, not as a means – in themselves – of bringing about learning’ (Nutbrown, 2006, p.126).

To read more about the principles and practices of assessment ‘as’ and ‘for’ learning, visit the teaching practice page.

Module 3.3: Assessment models

Discussing assessment cycles

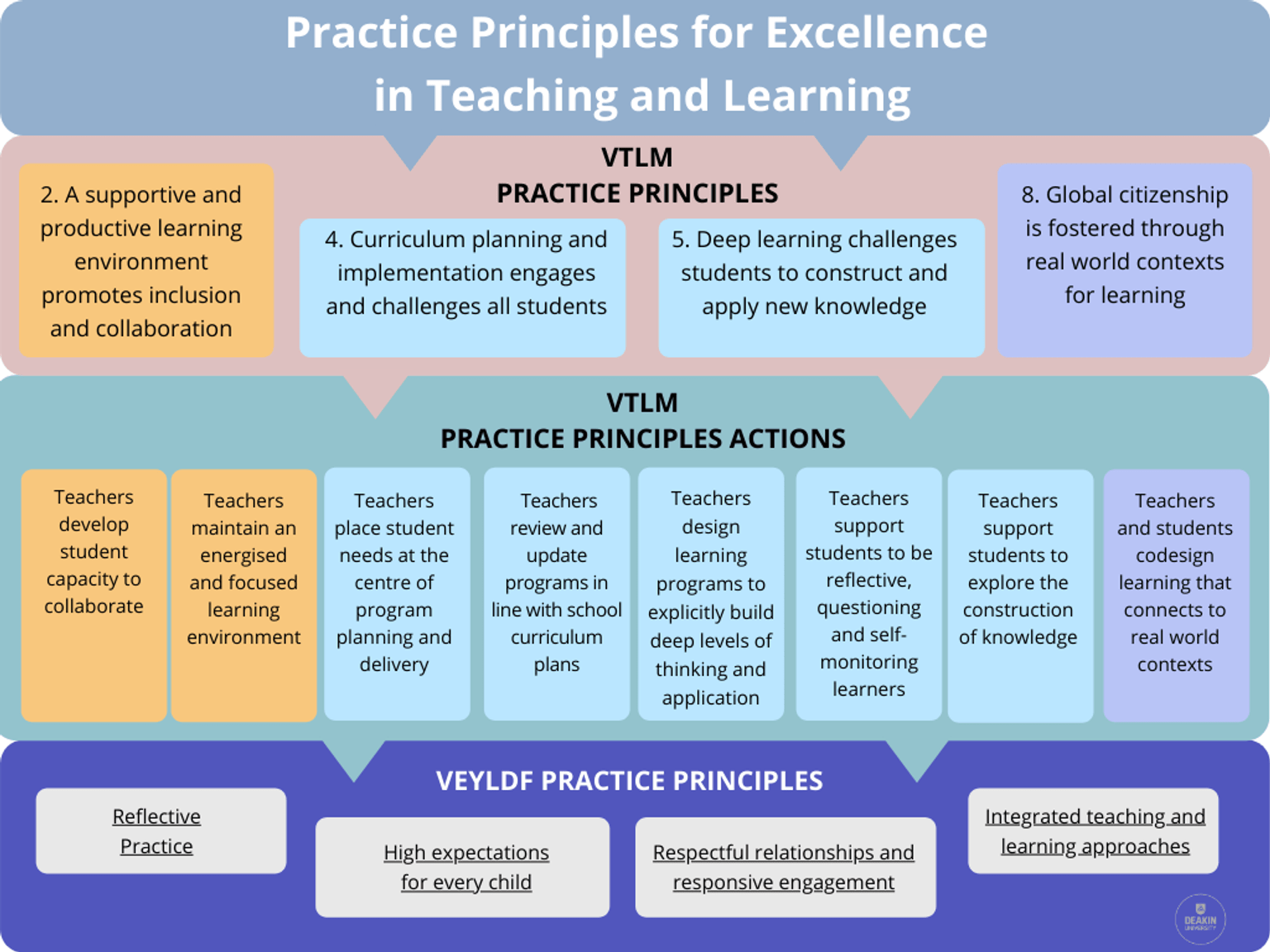

The Victorian Teaching and Learning Model (VTLM) practice principle 6 for excellence in teaching and learning (PDF, 1.2MB)(opens in a new window) expects rigorous assessment practices and feedback to inform teaching and learning. This practice principle notes the need for assessment to be authentic and designed for specific purposes.

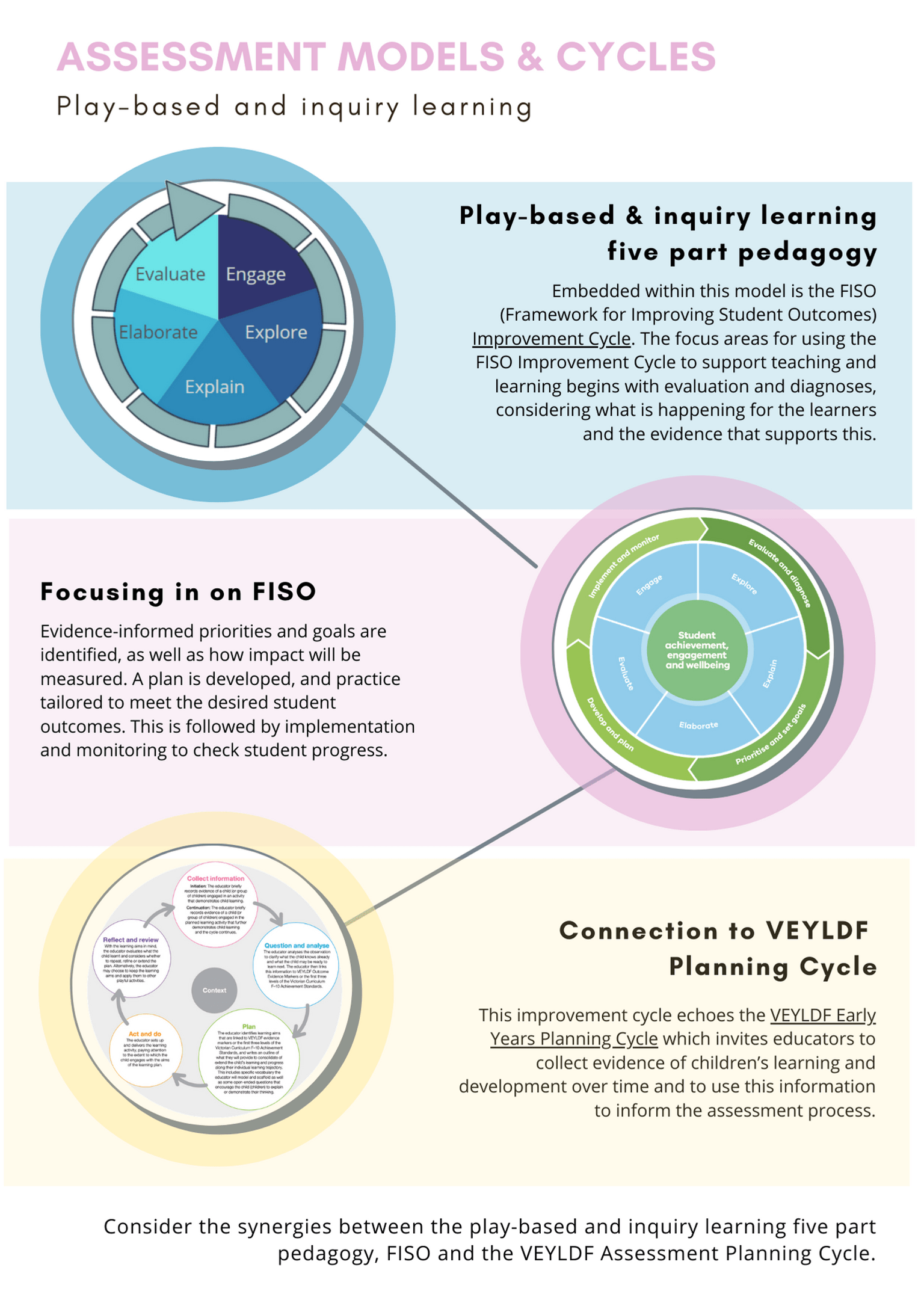

In Module 2 you were introduced to the pedagogy underpinning the VTLM(opens in a new window). The play-based and inquiry learning five-part pedagogy highlighted the domains of Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate and Evaluate. This is further explored in the infographic below, which focuses on the Framework for Improving Student Outcomes (FISO) Improvement Cycle(opens in a new window) and the VEYLDF Planning Cycle(opens in a new window).

Intersection between the Victorian Teaching and Learning Model (VTLM) and the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF)

To understand the intersection between the VTLM and the VEYLDF watch the ‘Introduction’ video of the VEYLDF Early Years Planning Cycle available on the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority website.

Watch the 'Introduction' video from VCAA website. In this video, Dr Caroline Cohrssen outlines the planning cycle resources developed by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority to guide planning and assessment.

Download the VCAA Early Years planning cycle resource(opens in a new window). Please note the document has been organised to reflect the different age groups of learners – birth to 2 years, 3 to 5 years and 6 to 8 years.

Play-based and inquiry learning supports High Impact Teaching Strategy 8: Feedback

The improvement and planning cycles discussed above position play-based and inquiry learning as an opportunity to provide students with informal and/or formal feedback to guide their current and future learning.

Thinking about learning goals

Learning goals are at the centre of a play-based and inquiry learning approach. Through your interactions with students in their play-based and inquiry experiences, you are able to redirect and/or refocus students’ actions, effort and activity towards a clear outcome that aims to achieve the set learning goal. Furthermore, the  VEYLDF Assessment for Learning and Development practice principle guide (PDF, 2.12MB)(opens in a new window) advocates that in play-based and inquiry learning, students can be encouraged and supported to take responsibility for their learning by contributing to the goal setting of their own learning (DET, 2016).

VEYLDF Assessment for Learning and Development practice principle guide (PDF, 2.12MB)(opens in a new window) advocates that in play-based and inquiry learning, students can be encouraged and supported to take responsibility for their learning by contributing to the goal setting of their own learning (DET, 2016).

During a play and inquiry learning experience, you can give students set tasks that require them to record their findings or write a narrative about their activity. Such documentation in hard copy form, provides an authentic opportunity to provide formal written feedback to students on their playful learning. We provide more information about feedback and reporting to support you to achieve HITS 8 in your play-based and inquiry learning approach.

Practice principles focus

The infographic below provides a visual poster of the connections between practice principles in the VTLM and the VEYLDF in relation to assessment. To further support your learning about the links between these documents with regards to assessment, you may find the VEYLDF illustrative maps useful(opens in a new window).

Module 3.4: Assessment of play

Assessing student's play

Assessing students’ play-based and inquiry learning, provides teachers with important information on how a student understands their world, how they interact with those around them, and how they build a narrative.

What’s the research telling us?

Research has shown that when a child can spontaneously initiate their own play, they have a “deeper understanding of the context of the play and are able to generate their play ideas across settings” (Stagnitti & Paatsch, 2018, p. 3). In addition, these children typically show strong competencies in oral language and demonstrate greater socio-emotional understanding and greater self-regulation (Elias & Berk, 2002; Whitebread & O’Sullivan, 2012; Whitebread et al., 2009).

As highlighted in the previous modules, play-based and inquiry learning is important for students’ development as it enables them to use their imagination to explore, experiment, discover, create, and collaborate with others. Play-based and inquiry learning also stimulates and integrates a wide range of intellectual, physical, social, emotional, and creative capabilities to foster high-level learning (DET, 2018). However, play-based and inquiry learning, particularly imaginary and dramatic play, is often not assessed for its own sake, but rather for the important learning that is taking place during these experiences (Thompson & Goldstein, 2019).

Reflecting on previous modules

Many researchers and teachers observe student outcomes such as creativity, self-regulation, social skills, language and literacy, theory of mind and social understandings during play (Lillard et al, 2013; Stagnitti, Paatsch, Nolan & Campbell, 2020). However, it is also important to assess the student’s level of play abilities from simple skills, such as manipulating objects and exploring their surroundings, to the more complex abilities to impose meaning on what they are doing and substituting an object for something else.

Assessing students’ imaginary and dramatic play

During imaginary and dramatic play, teachers can observe the student’s level of play development and can use these observations to report to parents and other teachers, to plan for future play sessions, and to determine their own role in supporting students to develop their play and inquiry learning abilities.

Observing and assessing imaginary and dramatic play

Teachers can observe imaginary and dramatic play in the following six imaginary and dramatic play skills (Stagnitti, 2021; Stagnitti & Paatsch, 2018). The interactivity below will provide you with further information.

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Privileging students' diverse capacities

Students enter school demonstrating many different play abilities. For example, some students will be able to play with a group of friends, negotiate, debate, and cooperate with others. Some students will be able to pretend to be someone else for an extended period, including understanding what that person would say, act and do. Many students will be able to use any object and pretend that it is something else and plan and develop a story that includes complex sequences with problems and resolutions.

Observing different types of play

Let’s watch the video of the four Foundation students and their teacher, playing with a set of animals, wooden blocks, fabrics, cars, trucks, sticks and gemstones. You watched this video in Module 1 to observe some of the different types of play as well as the learning that was taking place through play-based and inquiry learning.

Watch this video again with a focus on two specific students:

- The young boy with red hair (Thomas*), and

- The young girl with blonde hair (Celeste*).

*Names are pseudonyms

Share your observations

What play skills do you notice with these students? Using the 6 imaginary and dramatic play skills you just explored earlier, consider the above video and assess these students’ play abilities. Click on the plus (+) icon in the corner of the Padlet screen, to make your contribution to the board.

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Module 3.5: Assessing language and literacy

Connections between play-based and inquiry learning and language and literacy development

As discussed in Module 1, research has shown that there is a strong relationship between play-based and inquiry learning and language and literacy development. Specifically, object substitution has been found to predict oral expressive and receptive language abilities (Stagnitti, Paatsch, Nolan & Campbell, 2020) and complex play sequences predict the emergence of early multi-word speech and narrative skills, such as story comprehension and story production.

Play has also been found to support the development of emergent reading and writing skills, semantic organisation, and narrative re-telling skills. As such, play also provides teachers with the opportunities to assess students’ speaking and listening, language and literacy skills, and sociodramatic play (interacting with others).

Thinking analytically about students’ imaginary and dramatic play

The following interaction focuses on a sample of students’ imaginary and dramatic play. We will analyse this sample to look closely at some language and literacy abilities demonstrated by the students.

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Assessing language and literacy

This video about assessing language and literacy presents some short segments from an experienced Foundation teacher, Marie, regarding how she assesses students’ oral language, stories, speaking and listening, vocabulary and reading throughout play-based and inquiry learning. Note how she views the affordances of play-based and inquiry learning to observe and assess students’ abilities and learnings.

Module 3.6: Assessing numeracy and mathematics

Making sense of the world mathematically

Assessment in mathematics and numeracy is more than forming judgements about a learner’s ability. It monitors the learner’s understanding of the mathematical language, concepts and skills and what they need to do to succeed.

Assessing mathematics through play

Mathematics has developed from our social activity and as a way of making sense of our world. Play-based and inquiry learning in its many forms involves students in mathematical experiences because mathematics is part of their world and everyday lives. This is why mathematics has practical or ‘real life’ applications that play-based and inquiry learning can reveal. It is also where we see students’ numeracy in action, as they draw on their mathematics skills and knowledge and use these purposefully in a range of situations.

Play promotes mathematics engagement

Mathematics learned through play and inquiry is holistic and capitalises on students’ interests, intrinsic motivation, curiosity and ability to self-direct their learning. Play-based and inquiry learning provides genuine choice for students and opportunities for them to engage with a wide range of mathematical concepts, processes and explorations. Explore these concepts further within the Victorian Curriculum Learning in Mathematics.

These experiences are enhanced when students have teachers who can set curriculum goals that are facilitated through play, and who can support students to recognise, build, extend, reflect on and represent the mathematics that has emerged from their play. Play-based and inquiry learning, therefore, develops students’ capacities to play with mathematical ideas, and to inquire into and experiment with mathematical possibilities (Kinnear & Wittmann, 2018), making them ideal environments for noticing and assessing the mathematics learning they employ.

Mathematical ideas shared during meaningful conversations

Teachers can see students playing with mathematics even when they are not playing with objects. Mathematical ideas lend themselves to play. Teachers can observe the conversations that take place between each other and teacher and student.

Assessing mathematics in play

Perry & Dockett (2010) highlight that for teachers to assess students’ mathematical knowledge and understanding in play, they need “…mathematical knowledge; understanding the nature of students’ play, particularly the characteristics of play that promote mathematical learning and thinking and awareness of the role of adults in promoting both play and mathematical understanding.” (p. 715). The teacher’s openness to the opportunities play presents for mathematics assessment is also important. Let’s look more closely at these ideas.

To assess, we have to know what to look for, and what learning can come next, so an understanding of mathematics and mathematical learning trajectories is central to effective assessment. The Numeracy Learning Progressions(opens in a new window) supports teachers to understand how aspects of numeracy develop over time, and to use this knowledge to inform learning activities.

Ways of assessing mathematics

Although free play provides opportunities for mathematics learning, play that best supports mathematics learning, includes scaffolded dramatic and make-believe play (Clements, Sarama, Layzer, Unlu & Fesler, 2020), and is characterised as guided, where students experience choice and control in their play while the teacher brings the mathematics in the play into focus. In this role, the teacher uses questioning and discussion to guide explicit and extended exploration of the mathematics the students are engaging with and supports them to make connections between the mathematics and their play (Lee & Ginsburg, 2009).

Let's take a look at different ways of scaffolding and assessing students learning in mathematics.

‘Key thought’

“Assessment for learning and development is a continuous process of finding out what children know, understand, and can do in order to plan ‘what next’, build on previous learning and support new learning.” (DET, 2017, p. 7)

Making learning visible

We can make students’ learning visible through the actions we take and the data we collect about what students do and create. Teachers need a range of strategies to gain access to students’ current and developing mathematical knowledge and thinking, beginning with what mathematics they notice students engaging within their play and inquiry.

Play and mathematics learning

Play for mathematics learning develops students’ mathematical ideas through their language use, as the development of mathematical language enables students to reflect on their learning. Student language use, along with observation, is, therefore, a key indicator for assessing mathematical knowledge and mathematical thinking. An article by Caroline Cohrssen from the ECA Blog ‘The Spoke’ (2018) encourages teachers to think carefully about the role of questions and conversation when assessing play in mathematics.

High order questions

An essential role for a teacher as students explore, play with, and inquire about mathematical ideas, is to talk. Questions, particularly higher-order questions, and conversations that promote thinking critically and reflecting on the mathematical ideas and actions students are using, provide opportunities for assessment of and for learning, and encourage students to represent and think about their mathematical ideas in different ways.

Mathematics develops in a context

Mathematics learning is a culturally embedded and socially mediated activity. Research has shown that children’s free and spontaneous play is also important in students’ development of mathematical graphics. Social play provides opportunities for students to draw from their cultural knowledge and create and use drawings, signs and representations to solve problems and make and communicate mathematical meanings (Worthington, 2020). These informal mathematical representations can be used to gain insight into students’ mathematical thinking, knowledge and understanding and can be harnessed by teachers, to assess their current knowledge and to use that assessment to plan for ways to promote further mathematical thinking.

Asking mathematically rich questions

As you look closely at the interactive poster, click on the + hotspot to take note of the category of each question and the question starter. How do these questions support your practice?

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Stepping into playful assessment: numeracy and mathematics

Strategies teachers can use, that lend themselves to play and inquiry contexts, include ways of sparking students’ dispositions for curiosity, pretence, sense of humour and playfulness (Gifford, 2005).

Research has found that statements made by the teacher, that engage these dispositions, provoke more discussion than questions, and statements can foster learning and provide opportunities for assessment.

For example, in a play scenario involving shop play, the following approaches and use of statements, could elicit students’ mathematical ideas and ways of thinking, where the students’ responses could be assessed against the Victorian Curriculum Mathematics Achievement Standards(opens in a new window):

- teacher wondering out loud: “I wonder where the boxes are that we need to build the shop shelves?” (VCMMG082 - Describe position and movement)

- teacher making deliberate errors: Picking up a box priced “5” with five dots on the box to represent it and paying for it with four counters. (VCMNA072 - Compare, order and make correspondences between collections, initially to 20, and explain reasoning)

- provocative statements: (in response to a small set of objects - “What a lot of bananas you’ve got! I think there’s 100!” (Achievement Standards - estimate the size of sets).

Putting the Illustrative Maps into practice

The VEYLDF Illustrative Maps align the VEYLDF and the Victorian Curriculum and support making connections between what we observe in play and assessment.

For example, Outcome 4: Children are confident and involved learners in the VEYLDF is a rich basis for mathematics and numeracy assessment, because it engages many of the skills and processes where students use mathematics for problem-solving, and in inquiry, experimentation and investigation.

We can assess mathematics and numeracy using Outcome 4 when we see, for example, students:

- applying a wide variety of thinking strategies to engage with situations and solve problems,

- creating and using representation to organise, record and communicate mathematical ideas and concepts, and

- making predictions and generalisations about their daily activities…and communicating these using mathematical language and symbols.

Playful mathematics

In this interactive presentation consider the mathematical vocabulary that students use in their play. Click the hotspot +

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Module 3.7: Assessing personal and social capability

Privileging personal and social capabilities

Personal and social capabilities allow students to be aware of the self, family and community. Such awareness contributes to children’s connectedness, acceptance and experience of positive reciprocal relationships.

Having a repertoire of prosocial behaviours is an important personal and social capability that contributes to students’ success in group situations, including friendships and classroom experiences (VCAA, 2019). In particular, the ability to self-regulate emotions, collaborate with, and resolve conflict are just three prosocial skills that are essential for students’ reciprocal relationships with peers and engage in classroom experiences.

Porter (2016) notes that when young students develop a range of prosocial skills, they are more likely to build positive relationships with peers. These peer relationships promote students’ feelings of belonging and acceptance, as well as positive self-esteem. Collectively, these personal and social capabilities and dispositions contribute to students being more likely to engage, learn and succeed in school.

Reflecting on Module 1

As discussed in Module 1, play-based and inquiry learning provides a way for students to practice, re-enact, and master a range of emotional and social ideas, feelings and experiences, to support their personal and social capabilities.

For example, when students take on the role of someone else in imaginary and dramatic play, they explore a range of emotions that support their capacities for empathy, abstract levels of thought and reflection, and prepare them emotionally and intellectually for the future (Wieder, 2017). These capabilities are important for students’ self-awareness and social awareness.

Metacognitive and self-regulatory skills

Students also develop metacognitive and self-regulatory skills that are important for higher-order thinking, creativity, planning and evaluating learning, and problem-solving (Whitebread, Coltman, Jameson & Lander, 2009). These are capabilities that are important for students’ self-management and social management.

In all types of play and inquiry experiences, students are involved in collaboration with peers which facilitates friendships, promotes pro-social behaviours and attitudes, and fosters the experience of responding to peer suggestions and resolving conflict (Scott & Panksepp, 2013).

In terms of social skills, it is important to be alert to the contribution of culture and language to learning. Barblett and Maloney (2010) note when assessing social skills, teachers need to understand that students bring their own cultural lens to their learning and social experiences which informs the ways they interact with others. While many differences may be well-known and obvious, there will be other unexpected areas of divergence.

Aligning the VEYLDF with the Victorian Curriculum

Many of these experiences in play align with student's Personal and Social Capability Outcomes(opens in a new window) in the Victorian Curriculum.

In the interactive vodcast below, Dr Natalie Robertson provides an overview of how you may notice personal and social capabilities in students’ play-based and inquiry learning by drawing on the VEYLDF Learning and Development Outcomes.

Click on the tiles to listen to discussions and think about students’ identity and wellbeing.

Note: This interactive element may not meet our minimum WCAG AA Accessibility standards.

Downloadable resource

Personal and social capability: self-awareness and management (PDF, 136KB)

Personal and social capability: self-awareness and management (DOCX, 32KB)

A downloadable resource has been created that provides you with an illustrative map of how you may assess students’ personal and social capability outcomes through play-based and inquiry learning experiences.

Teachers talk about the assessment of personal and social capabilities

In this video about the assessment of personal and social capabilities, teachers from Wales Street Primary School explain how they notice, assess and document students’ personal and social capabilities. As you are watching this video, think about how the teachers are following the process of the VEYLDF Early Years Planning Cycle.

Module 3.8: Building community

Updated